Learning that the GDPR applies to paper records might come as a surprise.

We get it. When one thinks of the General Data Protection Regulation, the first image that comes to mind isn’t exactly one of dusty old typewritten forms, right? Given the importance of the internet in our everyday lives and the fact that most data processing happens through electronic means, one would be excused for thinking the GDPR doesn’t bother itself with paper records.

Yet, the reality is more complicated. As we’ve seen in the first installment of our GDPR guide, the Regulation’s goal is to protect personal data – in whatever form it might come.

As a result, even data kept on paper and processed manually can fall under the GDPR’s scope – as long as said data is part of a relevant filing system.

The Underrated Relevance of the Relevant Filing System

Relevant filing systems are first mentioned by Article 2(1) GDPR.

In laying down the Regulation’s material scope, the provision stipulates the GDPR shall apply to:

- the processing of personal data carried out in whole or in part by automated means (i.e., electronically), and

- the processing of personal data carried out manually, as long as the personal data forms part or is intended to form part of a filing system.

As you can see, establishing whether the data contained in your paper records forms part of a filing system is a big deal. If it does, the GDPR will apply (provided you fall under its territorial scope). If it doesn’t, kudos: you don’t have to worry about the Regulation.

But What’s a Filing System, Exactly?

Given the importance of the notion we’re discussing, one would expect the GDPR to provide a clear and comprehensive definition.

And Article 4(6) GDPR does offer a “relevant filing system” definition. But in our humble opinion, calling it “clear and comprehensive” is a bit of a stretch.

According to the article in question,

«‘filing system’ means any structured set of personal data which are accessible according to specific criteria, whether centralised, decentralised or dispersed on a functional or geographical basis.»

Basically, the clause tells us that if you’ve collected personal data (for reasons that are not purely personal) and organized it in batches according to any specific criterion, you have a filing system – and the data forming part of, or intended to form part of this system, must be processed in accordance with the GDPR.

But there is just as much the article doesn’t tell us.

What counts as a “structured set”?

What are examples of “relevant criteria”?

Does ordering the information in chronological order make the data “accessible according to specific criteria,” or is something more required?

And what if you stuff all the info under a “miscellanea” label?

Relevant Filing Systems as Defined by the CJEU

To (try to) answer those questions, we need to take a step back and examine what to date is the most relevant judgment dealing with the notion of “relevant filing system.”

A little background: the notion we’re dealing with predates the GDPR. It appeared verbatim in Directive 95/46 (i.e., the instrument that regulated personal data in the EU before the adoption of the General Regulation).

In 2018, a case dealing with Directive 95/46 was brought before the Court of Justice of the European Union (from now on, the CJEU).

The Finnish High Court had been required to pronounce whether Jehovah’s Witnesses had violated the Directive by collecting information during door-to-door activities. To do so, the Finnish Court had to ascertain whether such information counted as personal data. In turn, to figure that out, they needed the CJEU to clarify some elements of the definition of personal data offered by the Directive, including the meaning of “relevant filing system.”

That’s why what became known as the “Jehovan case” is so important for us: even though the CJEU didn’t deal exclusively with relevant filing systems, the judgment remains the most authoritative interpretation of the notion.

The CJEU and Relevant Filing Systems: the Importance of Easy Retrieval

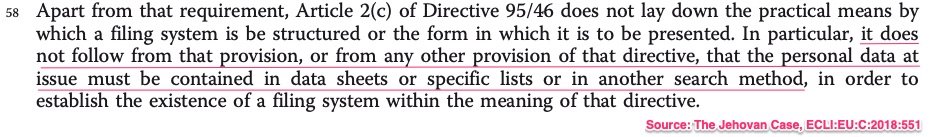

Building from the wording of recitals 15 and 27 of Directive 95/46, the CJEU found (par. 57) that:

«[…] the content of a filing system must be structured in order to allow easy access to personal data. Furthermore, although Article 2(c) of that Directive does not set out the criteria according to which that filing system must be structured, it is clear from those recitals that those criteria must be ‘relat[ed] to individuals’. Therefore, it appears that the requirement that the set of personal data must be ‘structured according to specific criteria’ is simply intended to enable personal data to be easily retrieved.»

The Court went on to add that enabling easy retrieval of personal data was the only requirement of a filing system.

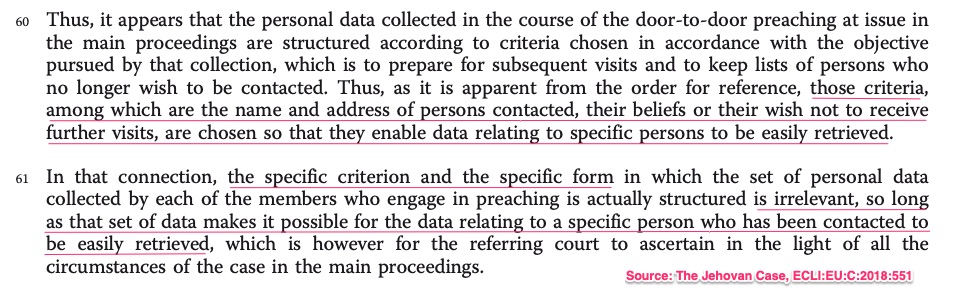

Moving from the general rule to the case’s specifics, the Court noted (par. 59) that the Jehovah’s Witnesses had collected names, addresses, and information related to the beliefs of the persons interviewed. The organization’s goal was to better prepare for subsequent visits by keeping lists of people who didn’t wish to be contacted again.

In other words, the preachers organized the information in a way that helped them find out who was interested in their activities and who wasn’t (specific criterion). By checking a name, the organization members could easily see whether they could or couldn’t be contacted again.

For the CJEU, that was enough to affirm the information was put in a filing system.

The Court concluded (par. 62) that a filing system could be discerned every time a set of personal data was structured «according to specific criteria which, in practice, enable them to be easily retrieved for subsequent use. In order for such a set of data to fall within that concept, it is not necessary that they include data sheets, specific lists or other search methods.»

Relevant Filing Systems as Defined by the ICO

“Jehovan” was the last time an EU organ discussed the notion of “relevant filing systems.” As of March 2022, neither the CJEU nor the EDPB have issued judgments or guidelines further elucidating the matter.

That’s unfortunate because the Jehovan Case left one huge question unanswered: when can we say that personal data is easy to retrieve?

The only way to answer this question is to turn to national data protection authorities, particularly to the work of the British Information Commissioner’s Office – a.k.a. the ICO.

The ICO is not an organ of the EU. Hey, it’s not even an organ of an EU Member State! So unless you are a UK citizen, nothing the ICO says directly impacts you. And obviously, neither the EDPB nor the CJEU are bound by the finding of the Information Commissioner’s Office.

You might be wondering, then, why do we bother with the ICO at all.

The fact is that, up to a couple of years ago, the UK was a Member State. And as such, it was legally obliged to enforce EU law – including first Directive 95/46 and then the GDPR.

The ICO was responsible for overseeing the application of these laws. In this capacity, it was frequently asked to clarify the meaning of some obscure clauses – including “relevant filing systems.”

And in doing so, the Office came up with a pretty helpful test.

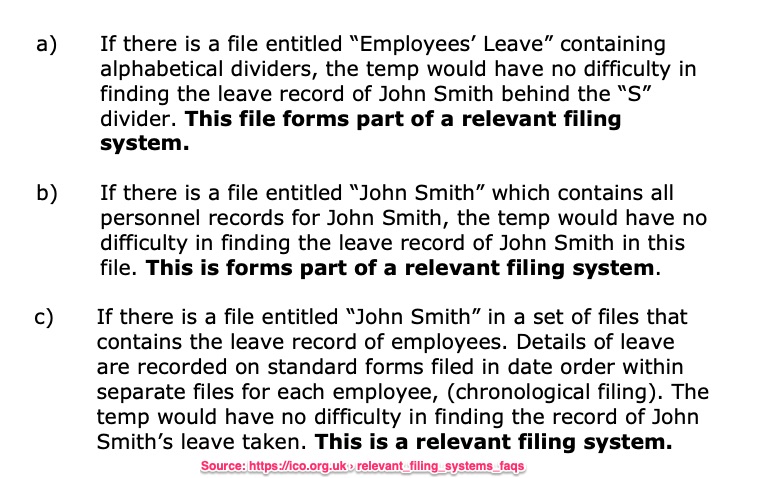

Relevant Filing Systems: The “Temp Test”

Building on the Jehovan judgment, the ICO holds that information about individuals must be easily retrieved for a filing system to exist.

But the authority then goes a step further. It devises a useful test to help data controllers understand whether the information they manually process can be “easily retrieved”: the “temp test.”

Under the “temp test,” information is considered “easily retrievable” if a temporary administrative assistant (a “temp”) can extract it from paper records without any particular knowledge of the data controller’s type of work.

Again, this is not an “official,” EU-sanctioned way to determine whether the information you hold is stored in a filing system. But it can help you better understand the concept.

Relevant Filing Systems: the Bottom Line

Understanding if the data you process forms part of a filing system is not a secondary task. In the case of manually processed data, it makes the difference between having to stick to the GDPR or not.

Unfortunately, the notion of “relevant filing system” is somewhat elusive. The GDPR talks about “any set of data organized according to specific criteria.” The CJEU has added that the data must be easy to retrieve without clarifying when that’s the case. The ICO tried to offer some guidelines, but it’s not an organ of the EU.

As with everything law-related, the best thing to do if you’re still in doubt is to consult with a lawyer specializing in Privacy or Data Law – and err on the side of caution.