If you know anything about the GDPR (and if you’ve ever surfed the internet after the Regulation went into force), you’ll know that consent is one of the legal basis for lawfully processing personal data.

What you might want to know is when consent can be considered valid.

In this article, we’ll see that valid consent is free, informed, specific and unambiguous – and we’ll explain what these notions mean for you as a data controller.

Finally, we’ll discuss other essential elements related to consent: the right to withdraw consent, the obligations of the data controller, and what to do when dealing with children.

Consent Requirements According to the GDPR

Consent requirements are spelt out by Article 4(11), according to which:

«’consent’ of the data subject means any freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.»

As we can see, there are four essential requirements for valid consent: freedom of choice, specificity, information, and lack of ambiguity. Let’s see what that means in detail.

Free Consent

When can we say that consent was freely given?

Both Article 4 and Article 6 are silent about it. Recital 42, however, states that “Consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment.”

The idea is fairly simple. Consent is not freely given when the data subject is forced to provide it or – a much more common instance – cannot refuse consent without facing detrimental consequences.

Is it always easy to draw the line?

Absolutely not. It’s a matter of nuance, and we recommend consulting a lawyer if in doubt.

However, the GDPR itself offers some useful guidance about what constitutes – and, critically, what doesn’t constitute – free consent.

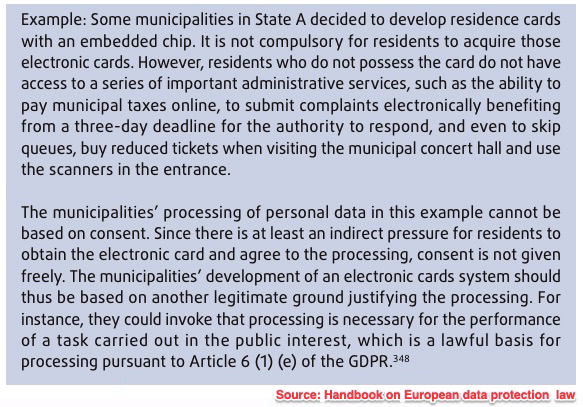

First, Recital 43 considers power imbalances, stating that «consent should not provide a valid legal ground for the processing of personal data in a specific case where there is a clear imbalance between the data subject and the controller.»

The provision refers mainly to cases where public authorities act as data controllers, and it’s less likely to apply to commercial relations between private citizens (or companies). But the principle underlying it remains valid: where there’s a clear imbalance of power in favor of the data controller, consent might not be considered as freely given.

(This doesn’t mean that consent will always be considered invalid in such cases, nor that processing cannot happen at all – data controllers can still rely on one or more of the other legal bases listed by Article 6. But, how can we put it? It’s better to err on the side of caution.)

Another important point Recital 43 makes is that consent should be as granular as possible to be considered as freely given. The provision states that

«Consent is presumed not to be freely given if it does not allow separate consent to be given to different personal data processing operations despite it being appropriate in the individual case, or if the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is dependent on the consent despite such consent not being necessary for such performance.»

A very similar idea underpins another GDPR provision, Article 7(4), according to which «When assessing whether consent is freely given, utmost account shall be taken of whether, inter alia, the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the performance of that contract.»

This might sound like a lot of legalese but bear with us.

The thing to retain is that you shouldn’t ask for personal data that’s not necessary for the performance of a specific contract (remember the principle of data minimization? That’s the idea).

If you force a data subject to unnecessarily give up personal data to enjoy a good or service, you have not obtained valid consent, and you cannot lawfully process that personal data.

Imagine running a brick-and-mortar grocery store. We come in and buy some food.

Do we need to share our personal data with you to complete the purchase? It depends. If we pay cash, no personal data comes into the equation. If we choose to use a credit or debit card, the answer might be different, but you still wouldn’t need to know our home address or phone number, right?

So if you did ask for our address or phone number (maybe because you want to send out marketing materials), and made the purchase conditional on our giving up that personal data, not only would you be extremely annoying and lose clients, but you’d be violating Article 7(4).

Because in the eyes of the GDPR, you are making the performance of a contract (i.e., buying groceries) conditional on consent to the processing of personal data (i.e., our address or phone number) that is not necessary for the performance of that contract.

TL;DR: give data subjects a choice. Don’t ask for personal data unless it’s necessary. And remember that power imbalances make it harder to demonstrate that consent was freely given.

Informed consent

To give valid consent, data subjects must know what they consent to.

Again, we can refer to Recital 42. The provision clarifies that consent can be considered informed when the data subject has been made aware at least of the identity of the data controller and of the purposes of the processing.

So if you are a data controller, it’s vital to tell your data subjects:

- Who you are (as you’ll be the one processing their data), and

- What will you do with the data? (use it for marketing purposes? Statistical purposes? or Something else? You have to tell them)

According to the Handbook on European data protection law, data controllers should also inform data subjects of what happens if they refuse consent.

If these conditions aren’t met, consent wasn’t informed, isn’t valid, and – unless you can rely on another legal basis – the processing is unlawful.

(So no, you cannot ask your customers to just “enter their email addresses” to get that lovely white paper without telling them what you will do with said email addresses. Yeah, tons of online businesses do. That doesn’t make it OK.)

Keep in mind that – in the words of the Handbook – “the quality of the information is important.”

The information you offer the data subjects should be clear, comprehensive, and easy to access. A jargon-filled, obscure privacy notice hidden in the depth of your website is not enough to make you GDPR-compliant.

TL;DR: Use clear, plain, and jargon-free language to inform data subjects of who you are and what you will do with their data. Make the information easy to find.

Specific consent

Granularity also comes into play when discussing the third requirement of valid consent: specificity.

Data controllers can’t ask data subjects to give consent once and for all.

Instead, they must clearly state for which purpose they are collecting personal data (as required by the purpose limitation principle). In addition, Recital 32 clarifies that when processing has multiple purposes, consent should be given for all of them.

If controllers need to change or add processing activities, consent must be asked again.

So it would be unlawful for you, as a data controller, to ask for a person’s address (personal data) without clarifying what you do with the data. If you only mean to send contractual information, you have to state it in clear, plain language.

If at a later moment you’d like to use that personal data for other purposes – for example, if you’d like to send marketing materials – you need to ask again for consent.

TL;DR: Consent is never universal. Explain to data subjects what they consent to (for processing purposes) in clear, plain language. Remember that you need to ask again for consent if you want to carry out other processing activities.

Unambiguous consent

Finally, to be valid, consent must be unambiguous, meaning there should be no reasonable doubt that the data subject wanted the processing to happen.

According to Recital 32, «Consent should be given by a clear, affirmative act […] Silence, pre-ticket boxes or inactivity should not, therefore, constitute consent.»

This wording is echoed by Article 4(11), which talks about «a statement or […] a clear affirmative action».

Consequently, inaction or silence cannot be considered unambiguous, valid consent.

Pay attention to what this means in practice. For example, according to the Handbook on European data protection law, formulas such as “by using our service, you consent to the processing of your personal data” are not admissible precisely because they rely on inaction instead of asking for an explicit declaration of consent.

(And yeah, that’s 85% of cookie banners out there).

TL;DR: Don’t rely on data subjects’ silence or inaction. Ask for affirmative consent.

GDPR & Consent: Other Things to Know

The right to withdraw consent

Article 7(3) explains that the data subject has the right to withdraw consent at any time (and as a data controller, you should inform them of such right). Consent should be easy to withdraw: in the words of the GDPR, it should be as easy as to give it.

Of course, the withdrawal doesn’t act retroactively: all processing activities carried out before consent was revoked are valid. From that moment on, you’d need to either rely on another legal basis or stop processing that person’s data.

Data processors must be able to demonstrate consent

As we’ve seen when talking about the GDPR principles, it’s not enough for data controllers to do the right thing. They must also be able to demonstrate their compliance at any moment.

The accountability principle also applies when it comes to consent. Article 7 of GDPR opens by stating that

«Where processing is based on consent, the controller shall be able to demonstrate that the data subject has consented to processing of his or her personal data.»

When children are concerned, special rules apply.

The GDPR devotes a whole article (Article 8) to consent requirements for children.

If you read the provision, you’ll see it refers to “information society services” offered directly to a child. In case you were wondering, “information society” is defined by another EU instrument (Directive 2015/1535) as “any service normally provided for remuneration, at a distance, by electronic means and at the individual request of a recipient of services.” It’s a fairly broad definition, covering most online services used by children.

According to Article 8 of GDPR, when an information society service is offered directly to a child, the processing is only lawful in two cases:

- The child giving consent was 16 or older, or

- The holder of parental responsibility (mother, father, guardian) gave or authorized the consent.

The Regulation is worded in the singular, so consent is valid when just one parent gave or authorized it. However, data controllers should make reasonable efforts to figure out whether the person giving consent is actually the holder of parental responsibility (and not, for example, an older brother or friend or the child themselves).

Member state law can lower the required age but not make it lower than 13 years.

GDPR & Consent: The Takeaways

The GDPR lists consent as a legal basis for processing (non-sensitive) personal data.

If data controllers want to rely on this legal basis (or if, in the absence of other lawful grounds, they have to rely on it), they must make sure that consent is free, informed, specific and unambiguous.

Controllers should also ensure they can demonstrate at any time that valid consent was given.

Finally, controllers should be careful when offering online services directly to children. The consent of a child aged 15 or less is not considered valid: controllers should only go ahead with the processing when a parent or guardian green-lighted it.