We know: talking about the GDPR’s definition of personal data must be among the dullest things ever.

So why don’t we spice up things with a quiz?

Under the GDPR, which of the following constitutes personal data?

- Your religion

- Your name and surname

- Your IP address

- Your email address

- Potentially all of the above

The correct answer is “5 – all of the above.”

If you got it right, kudos.

You’re not alone if you wonder how IP addresses can be personal data. As we’ve seen, the idea that “personal data” is narrowly construed is one of the biggest myths surrounding GDPR.

The fact is, “personal data” is a legal concept. As such, every legal system fills it with a different meaning.

What counts as personal data in – say – the US might not count as personal data in the EU and vice-versa. That’s why you always have to refer to the definition offered by the legal system you are dealing with.

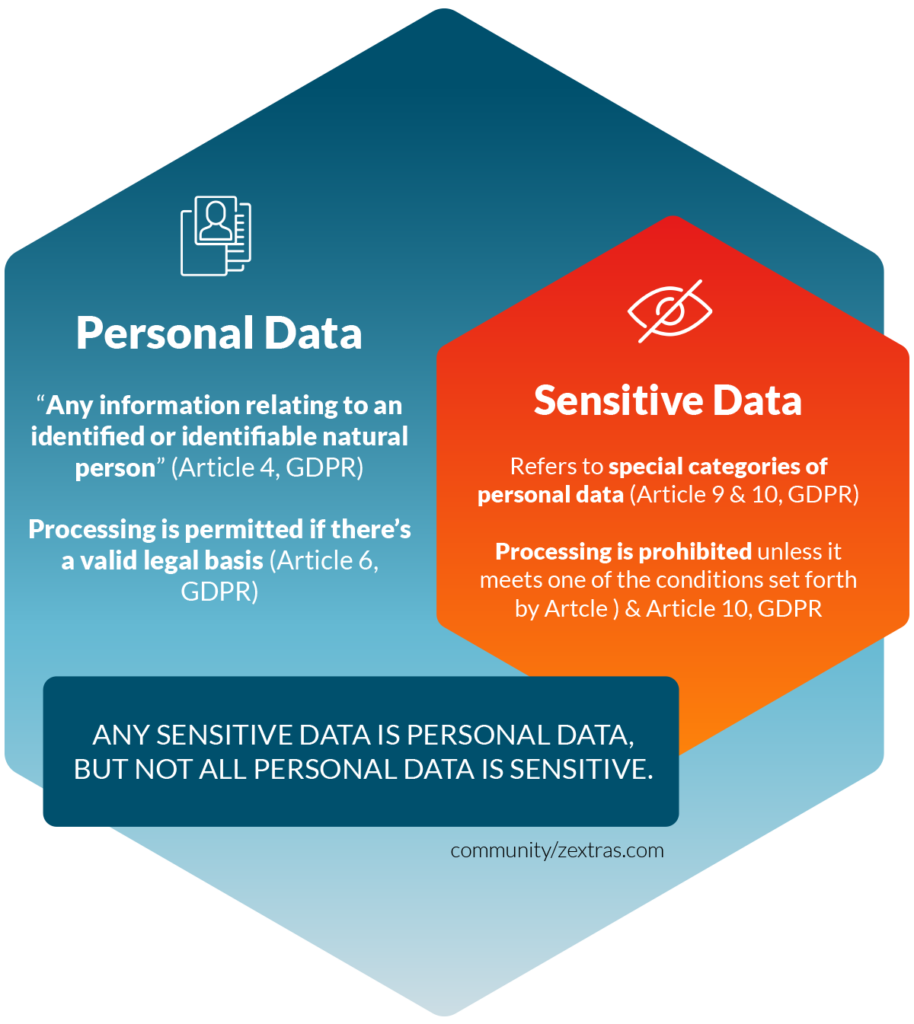

And that’s what we’ll do in this article: we’ll explore how the GDPR defines “personal data” (spoiler: it’s not synonymous with “sensitive data”).

How the GDPR Defines “Personal Data”

According to the definition offered by article 4(1) GDPR, personal data means:

«[…] any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’) […].»

Let’s break it down. Personal data is:

- Any information

- Relating to a natural person (called “data subject”)

- Who is either identified or identifiable.

Any Information …

That’s where most people get confused. They think “personal data” refers to some special category of particularly sensitive data and don’t associate the term with license plates, email addresses, or location data.

But this misconception can be misleading and damaging – because the GDPR states that any information can amount to personal data. No special qualifier is required.

It’s not even necessary for personal data to be hard facts.

As clarified by the 2018 EU Handbook on European Data Protection Law, opinions can also amount to personal data.

Nor is the concept limited to a natural person’s private sphere.

Data concerning activities of a professional nature also counts as personal data, as the CJEU (Court of Justice of the European Union) confirmed in the 2010 Volker und Markus Schecke and Hartmut Eifert v. Land Hessen case.

All that leaves us with a very broad definition, covering pretty much anything one can think of about a natural person (name, address, telephone number, face, age, sex, etc.) and even a few things one wouldn’t normally associate with this notion (email address, IP, location data).

Relating to an identified or identifiable natural person

So, any kind of information can amount to personal data – as long as it relates to a natural person who’s either

- identified (meaning their identity is clear), or

- Identifiable (meaning their identity can be established using additional information).

Both categories of data receive the same level of protection.

Now, the concept of “identifiable natural person” is tricky.

The GDPR defines it as « [a person] who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.».

Yeah, we know: it’s not the kind of definition that helps dispel doubts.

So forget about it for a moment and think about license plates instead.

By looking at a license plate, can you tell who the car belongs to?

Obviously not: a license plate is not the same as a name, surname, or ID picture.

But can you, with the help of additional information, establish the identity of the car owner?

Yup – in most cases, you can. Consequently, the person owning the car is identifiable, and the information relating to them is considered personal data.

As if we hadn’t ruined your day enough, it’s worth noting that what makes a person “identifiable” varies depending on several factors, including the technology available. Elements that, as of now, do not make a person “identifiable” (and thus don’t constitute personal data) might fall under this category in the future.

Special Categories of Personal Data

As a general rule, personal data can only be processed if the data controller has a valid legal basis – such as consent or legitimate interest – for doing so.

This protection is further reinforced when it comes to a special category of personal data: the so-called “sensitive data” (Notice that Article 9 speaks more generally of “special categories of personal data”; the expression “sensitive data” is found in Recital 26, GDPR).

Because of its nature, processing this data might result in harm or danger to the data subjects. Consequently, Article 9 states that all processing of sensitive data is prohibited – unless it meets one of the requirements set forth by Article 9(2).

Examples of sensitive data include:

- Data revealing racial or ethnic origin;

- Data revealing political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs;

- Data revealing trade union membership;

- Genetic data;

- Biometric data;

- Data concerning health;

- Data concerning a natural person’s sex life or sexual orientation.

Data relating to criminal convictions and offenses also benefits from additional safeguards. According to Article 10 of GDPR, its processing may only be carried out:

- If either EU or Member State law authorizes it; and

- Under the control of the official authority.

What’s NOT Personal Data Under the GDPR’s Definition

You might get the impression that pretty much everything amounts to personal data. And you wouldn’t be that far from the truth (academics have speculated that if the trend continues, in the future every piece of information will be considered “personal data”).

But under the GDPR, there are at least three significant categories of information that are not considered “personal data.” They are:

- Data relating to deceased natural persons;

- Data relating to legal persons; and

- Anonymized data.

Data relating to deceased natural persons

Recital 27, GDPR, clearly affirms that:

«This Regulation does not apply to the personal data of deceased persons. Member States may provide for rules regarding the processing of personal data of deceased persons.».

Just to clarify: the personal data of deceased persons is not fair game. But protecting it is beyond the scope of the GDPR.

Data relating to legal persons

As we’ve seen when discussing Article 1, the GDPR is concerned with protecting natural persons. Therefore, data relating to legal persons (companies, organizations, etc.) is not personal data.

Let’s clarify this distinction with an example. Let’s take two email addresses: john.brown@company.com and info@company.com, respectively.

The former relates to an identified natural person (Mr. John Brown, working at Company) and thus qualifies as personal data under the GDPR.

The latter is a generic email address relating to a legal person (Company). Obviously, there’s a natural person behind it, but we have no way to identify them. Thus, the GDPR doesn’t consider it personal data.

Anonymized data

Personal data is anonymized when all the identifying elements are irreversibly eliminated, to the point that the data subject is no longer identifiable. If the anonymization process has been completed, that data no longer counts as personal data.

The GDPR doesn’t recommend a specific technique for anonymizing data. The Regulation is more concerned with results than with methods. As long as anonymization makes re-identification impossible, data controllers are free to choose the solution that works best for them.

Keep in mind that anonymization has to be permanent. If some elements left in the information allow re-identification of the data subject, the data is still considered personal data.

Pseudonymization

Anonymization shouldn’t be confused with pseudonymization.

Article 4(5) GDPR defines pseudonymization as «the processing of personal data in such a manner that the personal data can no longer be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information, provided that such additional information is kept separately and is subject to technical and organisational measures to ensure that the personal data are not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person.»

Unlike anonymized data, data that has undergone pseudonymization can still lead to the re-identification of the data subject.

To give you an example, let’s take what’s arguably the most common way to pseudonymize personal data: encryption.

Encrypted data can’t be attributed to a particular data subject without the decryption key (the “additional information” mentioned in article 4). However, the identifying elements have not been irreversibly eliminated: whoever uses the decryption key (legally or illegally) can easily re-identify the data subject.

As the Handbook on European Data Protection Law clarifies, “pseudonymized data” does not constitute a special category under the GDPR. Data that has undergone a pseudonymization process – including encrypted data – is considered personal data and treated as such.

Conclusion: “Personal Data” is Not the Same as “Sensitive Data”

Under the GDPR, any piece of information relating to a natural person can count as “personal data.” The definition is everything but narrowly construed.

Data controllers should be careful when assessing whether they are processing personal data. In particular, they should be aware that personal data and sensitive data are not synonyms.

Sensitive data (as identified by Article 9 and Article 10, GDPR) is a special category, receiving additional protection by virtue of its complex nature.

But if you are a data controller, keep in mind that all personal data has to be processed according to the GDPR’s core principles.